Polish Poetry Unites is a video series for anyone interested in literature, history and reading. In each episode Edward Hirsch, a distinguished American poet, and the president of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, will introduce a celebrated Polish poet to American audiences.

Watch the episode on YouTube channel.

This episode of Polish Poetry Unites introduces the work of Adam Mickiewicz to American audiences. Mickiewicz was born in 1797 in Zaosie [now Belarus] and died in 1855 in Constantinople [now Istanbul], Turkey, where he went to help organize Polish forces under the Ottoman Army to fight Russia in the Crimean War. Adam Mickiewicz was one of Three Bards, the national poets of Polish Romantic literature. The term is almost exclusively used to denote Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński. Of the three, Mickiewicz is considered the most influential. Following the exploration of Mickiewicz’s life and poetry by Edward Hirsch (more below) the video showcases the story of Tadeusz Jaskółowski, a “handyman” as he calls himself, who is presenting his favorite poem, To M. by Adam Mickiewicz. Edward Hirsch said: “Adam Mickiewicz is the greatest 19th century romantic poet from Poland, or Polish poet. He’s a national hero. He believed strongly in Polish independence and liberty. I suppose one of the interesting things about Mickiewicz as the greatest Polish poet of the 19th century is that he was born in what is now considered Belarus, this was once part of Lithuania or the Duchy of Lithuania (part of the Polish Commonwealth), a bond between Poland and Lithuania, so I guess the greatest Polish poet is also the greatest Polish–Lithuanian–Belarussian poet. What I would say is the land was Lithuanian, but the ideal, the dream of unity and freedom was completely Polish, and he wrote in Polish. He wrote the greatest Polish epic, Pan Tadeusz, which is what I suppose he’s best known for, there is a terrific translation in English by Bill Johnston. It sort of sets the terms of Polish identity in a certain way. Not everyone was a fan, Gombrowicz was a skeptic, he thought the ideas of Polish gentry and unification were a bit puerile, but Czesław Miłosz was a follower. If you want an introduction to Mickiewicz’s work, I will highly recommend Miłosz’s section on him in History of Polish Literature, which is where I first heard about Mickiewicz. Mickiewicz was also a political poet. I’m a fan of his Crimean sonnets and for our purposes he was also a great love poet, something like Byron, and in the film, the former farmer, now a handyman, jack of all trades, he seems to be able to fix anything, recites from memory Mickiewicz’s wonderfully sad, longing, beautiful love poem, To M and he remembers how as a shy boy he used to recite this poem to try and woo a lover. It’s a time-honored tradition in Latin America, Neruda’s Twenty Love Songs and a Poem of Despair (actually, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair) used by thousands of young people to woo each other and in Poland it was Mickiewicz’s wonderful love poems, you can read them in English in a terrific book called Treasury of Love Poems by Adam Mickiewicz. And it shows Mickiewicz’s range as a love poet, he’s also a political poet and he’s the greatest poet of Polish independence and the dream of freedom and Poland’s contribution to European ideals and values.”

To M.

Away from my sight! I’ll listen instantly,

Away from my heart! My heart will obey,

Away from my memory! No, this order

Neither my memory nor yours will obey

As shade that’s longer, when cast from far away,

Makes the mourning circle much wider sprawl…

So will my figure, the further off I stay,

Becloud your memory with a thicker pall.

In every place and at each time of day,

Where I cried with you, where we played together,

Everywhere and always next to you I’ll stay,

For part of my soul, I left in each quarter.

Whether deep in thought in secluded chamber,

Close to your harp by chance you’ll come along.

Then you will recall: at this exact hour

I was singing for him the very same song.

Or playing chess, when in the first foray

Your king was trapped in the deadly campaign,

Then you will think: the ranks stood in this way

When we came to the end of our last game.

Or at ball, when to rest you sit aside,

Ere the musician announces the next dance,

You will see an empty place by fireside,

And you will think: he sat with me there once.

Or when you read a book and will descry

The lovers’ hope wrecked by a dreadful chance,

You will put it down and with a deep sigh

You will think then: ah, it is our romance…

And if the author after a tangles plot

Let the loving pair join at last together,

You will put out the candle and dwell on the thought:

Why didn’t our tale end this way ever?

All at once lighting will flash in the night,

Dry pear tree leaves will rustle in the orchard,

The moaning owl will brush the pane in its flight…

You will think then that it is my spirit.

So in every place and at each time of day,

Where I cried with you, where we played together,

Everywhere and always next to you I’ll stay,

For part of my soul I left in each quarter.

translated to English by J.M Mikoś, from the collection: Treasury of Love Poems by Adam Mickiewicz edited by Krystyna Olszer, and published by Hippocrene Books

Do M.

Precz z moich oczu!… posłucham od razu,

Precz z mego serca!… i serce posłucha,

Precz z méj pamięci!… Nie! tego rozkazu

Moja i twoja pamięć nie posłucha.

Jak cień tém dłuższy, gdy padnie z daleka,

Tém szerzéj koło żałobne roztoczy,

Tak moja postać, im daléj ucieka,

Tém grubszym kirem twą pamięć pomroczy.

Na każdém miejscu i o każdéj dobie,

Gdziem z tobą płakał, gdziem się z tobą bawił,

Wszędzie i zawsze będę ja przy tobie,

Bom wszędzie cząstkę méj duszy zostawił.

Czy zadumana w samotnéj komorze

Do arfy zbliżysz nieumyślną rękę,

Przypomnisz sobie: właśnie o téj porze

Śpiewałam jemu tę samę piosenkę.

Czy grając w szachy, gdy piérwszemi ściegi

Śmiertelna złowi króla twego matnia,

Pomyślisz sobie: tak stały szeregi,

Gdy się skończyła nasza gra ostatnia.

Czy to na balu w chwilach odpoczynku

Siędziesz, nim muzyk tańce zapowiedział,

Obaczysz próżne miejsce przy kominku,

Pomyślisz sobie: on tam ze mną siedział.

Czy książkę weźmiesz, gdzie smutnym wyrokiem

Stargane ujrzysz kochanków nadzieje,

Złożywszy książkę z westchnieniem głębokiem,

Pomyślisz sobie: ach, to nasze dzieje…

A jeśli autor po zawiłéj probie

Parę miłośną na ostatek złączył,

Zagasisz świécę i pomyślisz sobie:

Czemu nasz romans tak się nie zakończył?…

Wtém błyskawica nocna zamigoce,

Sucha w ogrodzie zaszeleszczy grusza,

I puszczyk z jękiem w okno załopoce…

Pomyślisz sobie, że to moja dusza.

Tak w każdém miejscu i o każdéj dobie,

Gdziem z tobą płakał, gdziem się z tobą bawił,

Wszędzie i zawsze będę ja przy tobie,

Bom wszędzie cząstkę méj duszy zostawił.

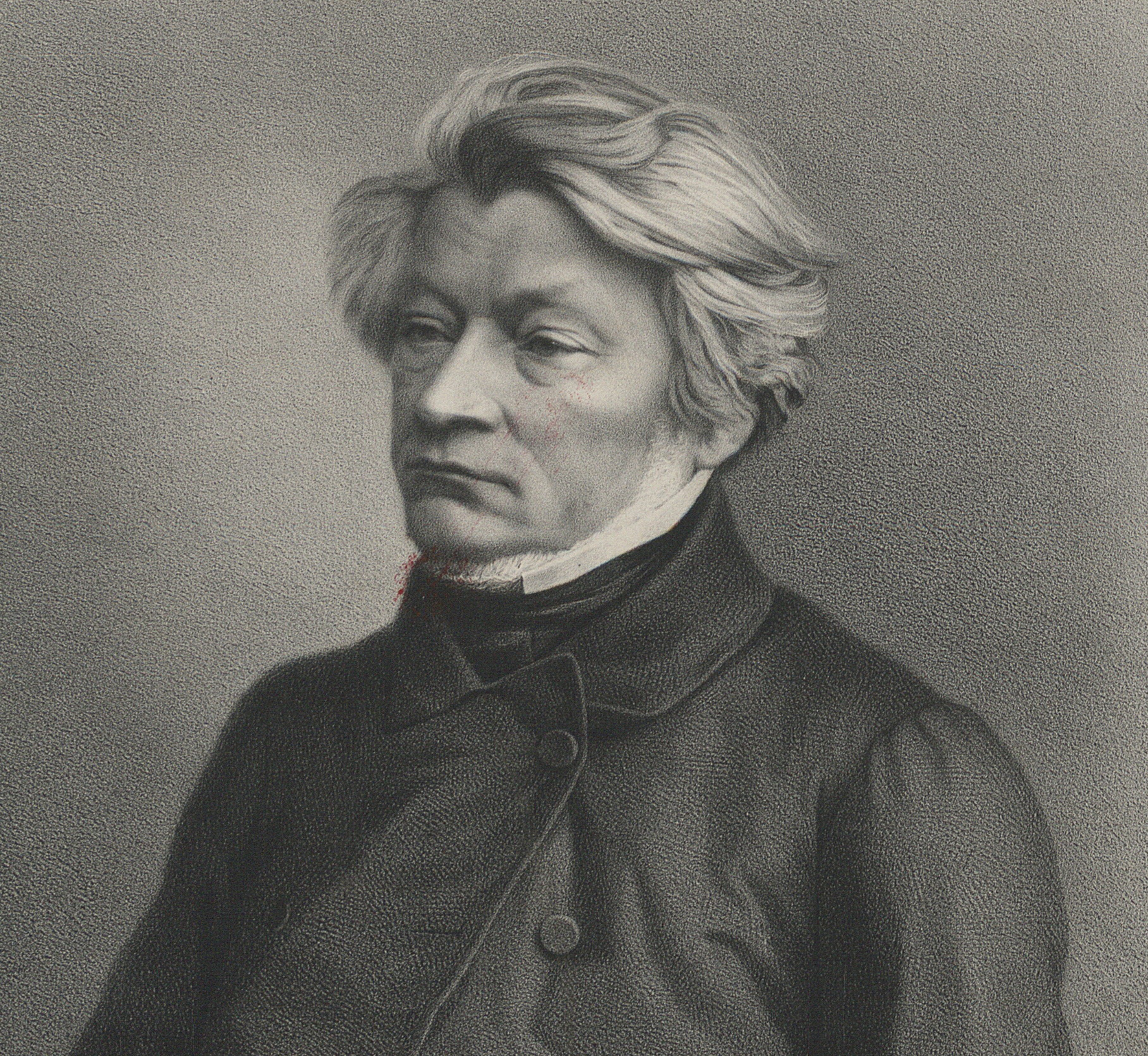

Adam Mickiewicz (born December 24, 1798, Zaosye, near Nowogródek, Belorussia, Russian Empire [now in Belarus]—died November 26, 1855, Constantinople [now Istanbul, Turkey] was one of the greatest poets of Poland and a lifelong apostle of Polish national freedom.

Born into an impoverished noble family, Mickiewicz studied at the University of Wilno (now Vilnius University) between 1815 and 1819; in 1817 he joined a secret patriotic student society, which was later incorporated into a larger clandestine student organization. Together with his fellow students in the organization, Mickiewicz was arrested in 1823 and deported to Russia for illegal patriotic activities. In Moscow he established friendly relations with Aleksandr Pushkin and other Russian intellectuals.

Mickiewicz’s first volume of poems, Poezye (1822; “Poetry”), included ballads, romances, and an important preface explaining his admiration of western European poetic forms and his desire to transplant them to Polish literature. The second volume of Poezye (1823) contained parts two and four of his Dziady (Forefather’s Eve), in which he combined elements of folklore with a story of tragic love to create a new kind of Romantic drama. While in Russia he visited Crimea in 1825, and, soon after, he published his cycle of sonnets Sonety Krymskie (1826; Crimean Sonnets). Konrad Wallenrod (1828; Konrad Wallenrod and Grazyna) is a poem describing the wars of the Teutonic Order with the Lithuanians but actually representing the age-old feud between Poland and Russia.

Mickiewicz was finally able to leave Russia in 1829, on the grounds of ill health. Traveling throughout Germany, he missed participating in the unsuccessful Polish insurrection of 1830–31. In the third part of Dziady (1833; Dziady III), which he completed in 1832, Mickiewicz views Poland as fulfilling a messianic role among the nations of western Europe by its national embodiment of the Christian themes of self-sacrifice and eventual redemption. In 1832 he settled in Paris and there wrote, in biblical prose, the Księgi narodu polskiego i pielgrzymstwa polskiego (“Books of the Polish Nation and Its Pilgrimage”), a moral interpretation of the history of the Polish people.

Mickiewicz’s masterpiece, the great epic poem Pan Tadeusz (1834; Eng. trans. Pan Tadeusz; film 1999), describes the life of the Polish gentry in the early 19th century through a fictional account of the feud between two families of Polish nobles. The poem conveys perfectly the ethos of an archaic society in which the ideals of chivalry are still alive and shows the effect of the Napoleonic myth on the minds of Poles for whom the French emperor and the Polish troops under his command represented the only hope for liberation from Russian rule.

Mickiewicz was appointed professor of Latin literature at the University of Lausanne (Switzerland) in 1839 but resigned a year later to teach Slavonic literature at the Collège de France. He remained there until 1844, when Napoleon III relieved him of the post—because he was teaching the mystical doctrines of the mesmerist Andrzej Towiański—and appointed him librarian at the Arsenal. In early 1848 he went to Rome to persuade the new pope to support the cause of Polish national freedom. Between March and October 1849, he edited the radical newspaper La Tribune des Peuples (“People’s Tribune”). In September 1855 he was sent to Turkey by Prince Adam Czartoryski to mediate between factions of Poles preparing to fight with the Allies in the Crimean War, but he did not survive the trip. In 1890 his remains were reburied in the vault of Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, where many Polish kings are laid to rest.

Biography source: Britannica.

More about Adam Mickiewicz:

https://culture.pl/en/artist/adam-mickiewicz

https://iam.pl/en/influence-adam-mickiewicz-poetry-that-acts

https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801444715/adam-mickiewicz/#bookTabs=1

https://allpoetry.com/Adam-Mickiewicz

https://culture.pl/en/article/translating-mickiewicz-polands-international-man-of-mystery

https://muzeumpanatadeusza.ossolineum.pl/en

https://culture.pl/en/article/adam-mickiewiczs-eastern-face

https://culture.pl/en/article/mickiewicz-the-zohar

https://culture.pl/en/article/the-ghost-of-mickiewicz

https://culture.pl/en/work/adam-mickiewicz-grazyna

https://culture.pl/en/work/ballads-and-romances-adam-mickiewicz

https://culture.pl/en/work/forefathers-eve-adam-mickiewicz-0

Edward Hirsch is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry entitled How to Read A Poem And Fall In Love With Poetry published in 2014. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010) and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker called “a masterpiece of sorrow.” He has also published five prose books about poetry. His latest book of essays, 100 Poems to Break your Heart was published in 2021. He is president of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York City. Currently he is finishing a book of essays called The Heart of American Poetry. It will be published in April to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Library of America. The book consists of deeply personal readings of forty essential American poems. It rethinks the American tradition in poetry. Ed Hirsch lives in New York City.

Lead image: Portrait of Adam Mickiewicz painted by Julian Mackiewicz | Public domain

Moderator: Edward Hirsch

Writer and Director: Ewa Zadrzyńska

Cinematography: Jacek Mierosławski and Mila Antoniszczak

Editor: Anna Jędrzejewska

Curator and Executive Producer: Bartek Remisko

The video about Adam Mickiewicz from the POLISH POETRY UNITES video series was realized with additional support from: New York Women in Film & Television and The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw.