Polish Poetry Unites is a video series for anyone interested in literature, history and reading. In each episode Edward Hirsch, a distinguished American poet, and the president of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, will introduce a celebrated Polish poet to American audiences.

Watch the episode on YouTube channel.

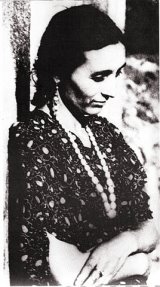

This episode of Polish Poetry Unites introduces the work of the Polish Roma poet Bronisława Wajs, known as “Papusza,” who is considered one of the most renowned Roma poets in the world today. Her work was first translated from Romani into Polish by the celebrated Polish poet Jerzy Ficowski (1924–2006). Other translations of Papusza’s oeuvre have recently followed. Edward Hirsch, who frequently explores the art of translation in his essays—devoting an entire chapter to it in his book A Poet’s Glossary —shares his views on this vital art form in the context of a discussion about the rules of translation, sparked by a recent academic publication in Polish that revealed significant discrepancies between the Romani original and its Polish translation.

The second part of the video features Dorota Czerner Richardson, a poet and translator currently working on translating Papusza’s poetry into English. Dorota presents one of Papusza’s poems in both Polish and English.

In the video, Edward Hirsch says: ‘I’ve been waiting for years for Papusza’s poems to be translated into English, and I’m very excited that they finally will be, so I can get a fuller sense of her as a poet. I love the poem, “Where are flowers in my skirt… where is my skirt with all of the flowers in the world.” What a poem. It has what the Portuguese call saudade, a nostalgia for something lost—and in this case, something gained, too. It’s really a poignant poem.

I can’t exactly weigh in on the recent controversy in Poland because I haven’t read the critical book. Nor can I, because I don’t know Polish. I can’t really read Ficowski’s translations. But it seems to me that the controversy is, from my point of view, a misunderstanding about the nature of translation itself. There’s been a long history of debate about translation in the world of poetry.

In my opinion, there’s a kind of sliding scale in translation. On one side, you have a very literal ‘trot’—an exact linguistic translation—and there are people who believe in this method. Vladimir Nabokov, for example, was a great believer in literal translation.

Nabokov was a great linguist, but his translation of Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin into English is completely unreadable—it’s just terrible. And this is coming from a great writer. The problem is that with a literal ‘trot,’ something that is exact linguistically, the whole soul of the poem is often lost. Languages just can’t be translated exactly—especially poetry, which is a kind of event where a lot of pressure is put on the language.

As poets, scholars and translators move away from the literal, they move toward something more like an adaptation—something that changes the poem to suit the target language. The far end of this spectrum is what John Dryden called ‘imitation,’ where the result is no longer really a translation but an imitation. Ezra Pound was a believer in this approach. He went so far, for instance, that his translations of Cavalcanti had to be called Homage to Cavalcanti because they were so far from the literal.

It’s my sense that Ficowski falls somewhere between the literal and imitation. He seems to be adapting Papusza’s poems into Polish and shaping them as poems. Translating a poet like Papusza is especially difficult because Romani culture is so protective and because the Romani language is primarily oral. Writing down poems is already considered a betrayal in some sense. Papusza paid a heavy price for writing and publishing her poems—and for having them translated. She was ostracized. Historically, any Romani poet who transitioned from oral to written poetry has been ostracized by their community, which is both patriarchal and deeply skeptical of outsiders.

For Papusza to be known at all, it requires someone to translate Romani culture itself and adapt these poems into a target language. In this case, the poems are going through multiple layers—from Romani to Polish, and then from Polish to English—so there’s an even greater distance. Some critics argue that this kind of translation is a form of appropriation. This is a recent critical theory, but I believe translation is at the root of culture itself.

Without translation, we wouldn’t be able to understand other cultures. Of course, you should learn the original language, if possible, but without translation, Japanese poets, for instance, would have been completely unknown to the Polish poets who admire them so much. Without translation, I wouldn’t be able to talk to you about Mickiewicz, Miłosz, Herbert, Szymborska, Różewicz, or any of the poets who have come after them—including one of my closest friends, Adam Zagajewski.

Translation is at the heart of culture. It must be done sensitively, and it’s always better when there are multiple translations so we can compare. The act of translation itself, however, is noble, even though it’s difficult and never perfect. There’s always something lost in translation that cannot be fully captured in the new language. Some poets are virtually untranslatable—I don’t think Papusza is one of them, but we’ll have to wait and see.

I’m so grateful to Dorota for taking on the task of translating these poems into English. I wish her the best of luck and very much look forward to seeing what she comes up with.’

More about Jerzy Ficowski

More about Papusza (in English):

Tears of Blood: A Poet’s Witness Account of the Nazi Genocide of Roma by Papusza / Bronisława Wajs

The Literary Work of the Roma in Poland Before and After Enforced Settlement by Emilia Kledzik

Bronisława Wajs, most widely known by her Romani name Papusza, was one of the most famous Romani poets of all time. She did not receive any schooling and, as a child, she paid non-Romani villagers with stolen goods in exchange for teaching her to read and write. At the age of 16 she got married off against her will to a man older than her by 24 years. Papusza survived the Second World War by hiding in the woods and became known as a poet in 1949, as a result of her acquaintance with Jerzy Ficowski, a poet and a translator from Romani to Polish. Her poetry, dealing with the subject of yearning and feeling lost, quickly gained her recognition in the Polish literary world.

Ficowski convinced Papusza that by having her poems translated from Romani and published, she would help improving the situation of the Romani community in Poland. However, Ficowski also authored a book about Roma beliefs and rituals, accompanied by a Romani-Polish dictionary of words, which he learned from Papusza. He also officially gave his support to forced settlement imposed on Roma by Polish authorities in 1953. As a result, Papusza was ostracised from the Roma community. Her knowledge sharing with Ficowski was perceived as a betrayal of Roma, breaking the taboo, and a collaboration with the anti-Romani government. Although Papusza claimed that Ficowski misinterpreted her words, she was declared ritually impure and banned from the Roma community. After an eight-month stay in a psychiatric hospital, Papusza spent the rest of her life isolated from her tribe. Ficowski, who genuinely had believed that the forced settlement of Romani people would better their life by eradicating poverty and illiteracy, later regretted endorsing the government’s policy, as the abandonment of nomadic life had profound implications on the Romani community.

Dorota Czerner (born 1966 in Wrocław, Poland) completed her studies in philosophy at the Sorbonne. An essayist, poet, translator. Since 2003, she has been a co-editor of “The Open Space magazine”, published in Red Hook, NY.

Dorota Czerner a poet who entangled her European roots with the Hudson River light. Her live performances, created in collaboration with contemporary classical composers and video artists, embrace the discovery of ecosystems built around and inside the poetics of the spoken word. Fireflies (for spoken voice, chamber ensemble, video, and electronics) — the three-part collective composition inspired by the natural phenomenon of synchronous fireflies with her libretto — had two realizations in The National Opera Center, NYC. Czerner’s current project, Story of the Face (2022), is built around a short play about female identity, masks, image and self-image, with which composer Jon Forshee constructs a dynamic landscape from the poet’s own voice, computer-generated sounds, and live acoustic instruments. Premiered at The Maverick Concerts in Woodstock, NY, in August 2022, it will be presented at the Electrowave in Colorado Springs, 2025.

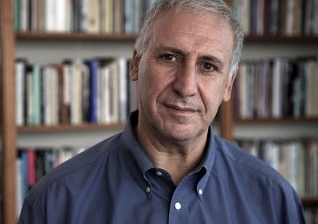

Edward Hirsch is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry entitled How to Read A Poem And Fall In Love With Poetry published in 2014. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010) and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker called “a masterpiece of sorrow.” He has also published five prose books about poetry. His latest book of essays, 100 Poems to Break your Heart was published in 2021. He is president of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York City. Currently he is finishing a book of essays called The Heart of American Poetry. It will be published in April to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Library of America. The book consists of deeply personal readings of forty essential American poems. It rethinks the American tradition in poetry. Ed Hirsch lives in New York City.

Lead image: Papusza | Public domain

Moderator: Edward Hirsch

Writer and Director: Ewa Zadrzyńska

Cinematography: Jacek Mierosławski and Mila Antoniszczak

Editor: Anna Jędrzejewska

Curator and Executive Producer: Bartek Remisko

The video about Adam Mickiewicz from the POLISH POETRY UNITES video series was realized with additional support from: New York Women in Film & Television and The Adam Mickiewicz Museum of Literature in Warsaw.