Films about Stanislaw Lem at The Cinematheque in Vancouver

June 4—July 1, 2021

More information about screenings and dates, availability and pricing:

http://thecinematheque.ca/series/lem-2021

“Lem 2021: Stanisław Lem on Film” is presented in partnership with The Cinematheque in Vancouver and co-programmed by Tomek Smolarski at the Polish Cultural Institute New York.

A giant of Polish literature, and of science fiction writing worldwide though in fact his work transcends the constraints of any particular genre Stanislaw Lem (1921-2006) produced dozens upon dozens of novels, stories, and essays throughout his nearly 60-year career. Best known for the writings that qualified, at least ostensibly, as science fiction, his body of work is dizzyingly multi-faceted, encompassing memoirs, reminiscences of his wartime experiences, and philosophical texts, while the science fiction narratives themselves often take wildly experimental forms and extend freely into the realms of philosophy and satire.

However, his work is characterized, one thing is for sure: Lem’s novels and stories have inspired (and continue to inspire) numerous filmmakers, with cinematic adaptations emerging from throughout the world, often helmed by some of the most important filmmakers past and present: from Andrei Tarkovsky and Andrzej Wajda to the Quay Brothers and Steven Soderbergh.

Organized in collaboration with The Cinematheque in Vancouver, this series offers a generous selection of these Lem-inspired cinematic works. Anchored by two versions of SOLARIS, Tarkovsky’s and Soderbergh’s celebrated films are joined by the selection of additional films whose diverse range of genres, tones, and stylistic approaches are entirely appropriate to Lem’s own body of work.

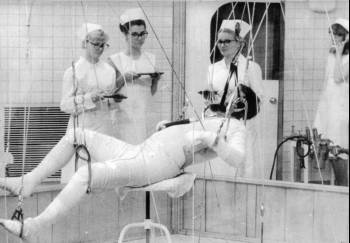

HOSPITAL OF THE TRANSFIGURATION

by Edward Zebrowski

In Polish and German with English subtitles, 1979, 90 min,

(SZPITAL PRZEMIENIENIA)

“Imagine ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST set in a Polish psychiatric hospital during the Nazi occupation. Such is the chillingly perverse scenario of this film, an adaptation of Lem’s first novel (written 1948, published 1955). Both novel and film utilize the asylum as a microcosm of society, but go a step further by placing that microcosm in a time and place – the early months of World War II – when the outer world itself had gone mad. The film anatomizes the beliefs, behavior, and identities of both patients and staff, seeking some principle, whether in reason or unreason, to oppose to the implacable totalitarian solution of involuntary euthanasia. But, as if always already overshadowed by the inevitable apocalyptic end, all intentions and actions degenerate into something akin to a piercingly tragic, cruelly humorous theater of the absurd. A disturbing, thoroughly ambiguous picture.” –Christopher J. Caes

PILOT PIRX’S TEST

by Marek Piestrak

In Polish, Russian, and Estonian with English subtitles, 1979, 95 min,

(TEST PILOTA PIRXA)

“Pirx the Pilot, the everyman of the space age, is one of Lem’s most beloved and psychologically complex characters, appearing over the course of nearly thirty years in ten short stories and one novel. The Estonian-Polish co-production, THE TEST OF PILOT PIRX, to date the only screen adaptation of a Pirx tale, is based on the 1968 short story “The Inquest.” In it, Pirx, no longer a bumbling space cadet but a seasoned star pilot, is approached by a corporation gearing up for the mass production of androids. The test: can Pirx determine which of the crew members under his command is an android and how he/it will perform under stress? Imagined against the backdrop of a slightly seedy, near-future corporatocracy and punctuated by composer Arvo Pärt’s edgy score, the film combines the sensibility of a spy thriller with the conceptual speculation of hard sci-fi.” –Christopher J. Caes

SOLARIS (Andrei Tarkovsky)

by Andrei Tarkovsky

In Russian with English subtitles, 1972, 166 min,

Certainly the most preeminent of Lem adaptations, Tarkovsky’s masterpiece centers on cosmonaut Kris Kelvin, who is dispatched to a space station orbiting the mysterious planet Solaris. Consisting of a vast ocean with mysterious, quasi-intelligent powers, this strange planet is able to materialize figures from the visitors’ past, forcing Kelvin to face his dead wife and to confront anew the circumstances that drove her to suicide. Though faithful to Lem’s novel in its central concept and in many of its particulars, Tarkovsky’s film is a radically different creature in terms of its tone and atmosphere, jettisoning much of Lem’s wit and satirical spirit. Nevertheless, the encounter between the disparate but brilliant sensibilities of Lem and Tarkovsky, is a fascinating one to behold, and the result is one of the greatest films of the 1970s.

“A towering movie…one of the most thoughtful science fiction epics ever and one of the few worthy successors to 2001.” –David Sterritt, CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

SOLARIS (Steven Soderbergh)

by Steven Soderbergh

2002, 99 min,

With George Clooney, Natascha McElhone, Viola Davis, and Jeremy Davies.

“The unique trajectory of Steven Soderbergh’s career takes him close to the stratosphere with his wholly unexpected and unexpectedly fine remake of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 SOLARIS, itself adapted from a first-rate novel of philosophical sci-fi by Stanislaw Lem. […] Solaris achieves an almost perfect balance of poetry and pulp. This is as elegant, moody, intelligent, sensuous, and sustained a studio movie as we are likely to see this season – and in its intrinsic nuttiness, perhaps the least compromised. Tarkovsky’s SOLARIS was the Russian visionary’s most pop movie; the remake, which draws on both Lem and Tarkovsky, is Soderbergh’s most avant.” –J. Hoberman, VILLAGE VOICE

AUTOR SOLARIS (Free of charge)

by Borys Lankosz

In Polish with English subtitles., 2016, 56 min, digital

This well-crafted and multi-dimensional documentary explores Stanisław Lem’s life and times, even as it charts the extent to which Lem’s writings and philosophy extended far beyond the time and place from which they emerged. Adopting many different methods, from archival material and interviews to dramatizations of scenes from both his life and his works, AUTOR SOLARIS is a penetrating portrait of the artist, and sheds light both on Lem himself and on the social and historical forces that helped shape him.

THE CONGRESS

by Ari Folman

2013, 122 min, digital

With Robin Wright, Harvey Keitel, Jon Hamm, Danny Huston, and Paul Giamatti.

Freely adapted from Lem’s 1971 novel, THE FUTUROLOGICAL CONGRESS, Ari Folman’s THE CONGRESS relocates the story to Hollywood, where aging actress Robin Wright (playing a version of herself) prepares to take on her final job: preserving her digital likeness for a future era. Through a deal brokered by her loyal, longtime agent (Keitel) and the head of Miramount Studios (Huston), her alias will be controlled by the studio, and will star in any film they want with no restrictions. In return, she receives healthy compensation so she can care for her ailing son, and her digitized character will remain forever young. Twenty years later, under the creative vision of the studio’s head animator (Hamm), Wright’s digital double rises to immortal stardom. With her contract expiring, she is invited to take part in “The Congress” convention as she makes her comeback straight into the world of future fantasy cinema.

“An extraordinary and very touching film that exists somewhere in the twilight zone between the existential brainteasers of Charlie Kaufman and the psychedelic wonders of Hayao Miyazaki.” –EMPIRE MAGAZINE

Stephen Quay & Timothy Quay (Free of charge)

MASKA

(2010, 23 min, digital. In Polish with English subtitles.)

Set to music by composer Krzysztof Penderecki, this Lem adaptation by the renowned animators the Quay brothers tells the story of an automaton, created in the form of a beautiful woman in order to assassinate a prince, who begins to question her purpose.

Andrzej Wajda

ROLY POLY / PRZEKLADANIEC

(1968, 35 min, b&w. With Bogumil Kobiela. In Polish with English subtitles.)

“[Wajda’s film] uses shots of Chicago skyscrapers to set in motion a bizarre futuristic story of a race-car driver who’s had so much of his body replaced by transplants that insurance companies question his very identity and he’s asked to support the children of one of his donors. Lem wrote Wajda that ROLY POLY ‘rekindled my trust in cooperation with film,’ and its amusing satire on the way people are constructed – and reconstructed – by technology and bureaucracy seems even more biting today.” –Fred Camper, CHICAGO READER

Return by Anna Blaszczyk, 2008, 8 min (Free of charge)

based on Lem’s book “Return from the Stars”. An astronaut returns to Earth after a very long space vacation. He discovers that time has flown faster at home and many things have changed while he was away. Will he still manage to fit in?

Mr. Lem was a giant of mid-20th-century science fiction, in a league with Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick. And he addressed many of the themes they did: the meaning of human life among superintelligent machines, the frustrations of communicating with aliens, the likelihood that mankind could understand a universe in which it was but a speck. His books have been translated into at least 35 languages and have sold 27 million copies.

What drew the admiration of many of his fellow writers was the intensity with which he studied the limitations of humanity, in ways that could be both awed and pessimistic.

In “Solaris,” a densely ruminative novel first published in 1961 — and made into films by Andrei Tarkovsky (1972) and Steven Soderbergh (2002) — contact is made with a dangerous and unknowable alien intelligence in the form of a plasma ocean surrounding a distant planet. As they attempt to understand the organism, astronauts aboard a space ship are plagued by hallucinations drawn from their own memories.

In “His Master’s Voice,” published in 1968, scientists in a Pentagon-sponsored project are similarly perplexed by a superior alien communication, this time from a pulsating neutrino ray. But the failed experiment gives the ill-tempered narrator, Peter Hogarth, a sense of wonderment: “The oddest thing,” he says, “is that defeat, unequivocal as it was, left in my memory a taste of nobility, and that those hours, those weeks, are, when I think of them today, precious to me.”

Born in 1921 in Lviv — then part of Poland but now in Ukraine — Mr. Lem began to study medicine as a young man, but his education was interrupted by World War II. He worked as a mechanic during the war and later returned to his medical studies but did not take his final exams out of fear that his services would be needed in the military. His first literary works were poems and short stories.

He emerged as a major science-fiction author in the early 1950’s with works that he later disavowed as simplistic, and he sometimes ran afoul of the Communist censors. In one early book, “The Cloud of Magellan,” he had wanted to write about cybernetics, a banned concept. “In order to get the novel through,” he told The New York Times in 1983, “I had to rename the field ‘mechanioristics’ — I created a new term.” An editor wasn’t fooled, and for a time, Mr. Lem said, the book remained unpublished.

Among his other works are “The Invincible” (1964) and “The Cyberiad” (1967). Some, like “Memoirs Found in a Bathtub” (1961) and “The Futurological Congress” (1971), are darkly satirical pictures of cold war-era life, involving technocratic societies that have broken down under the weight of their advanced machines.

Mr. Lem sometimes ridiculed his chosen genre. In “His Master’s Voice,” Hogarth, in an effort to come up with new ideas, tries reading some science-fiction stories but dismisses them as “pseudo-scientific fairy tales.”

Some of his most ambitious works drifted into experimental and philosophical territory. “Summa Technologiae” (1964) is a speculative survey of cybernetics and biology, and “A Perfect Vacuum” (1971) is a self-conscious experiment in meta-fiction, a set of reviews of 16 nonexistent books. One of the books reviewed is “A Perfect Vacuum” itself. “Did Lem really think,” the review reads, “he would not be seen through all this machination?”