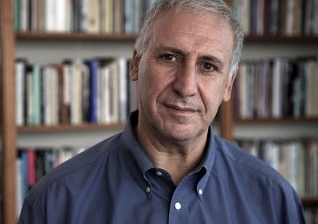

Polish Poetry Unites is a video series complementing our Encounters with Polish Literature series for anyone interested in literature, poetry in particular, history, and reading. In each episode, Edward Hirsch, a distinguished American poet, and the president of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, will introduce a celebrated Polish poet to American audiences.

Edward Hirsch says: Julian Tuwim (1894-1953) is a remarkable poet. He’s probably the most important Polish poet between World War I and World War II. He was a Jew and a Pole. He wasn’t very committed to his Jewishness; he was tremendously committed to his Polishness. He believed in the Polish literary and cultural tradition and contributed a tremendous amount to it. He was one of the founding members of a group called Skamander.

This group was vital and completely committed to the present. They believed in a kind of vital Bergsonian commitment to life. They were also traditionalists poetically, they believed in the sanctity of a good rhyme, in the importance, almost the divine quality of rhythm. The– the nature of poetic form. This makes their work extremely difficult to translate, said Edward Hirsch in the beginning of his introduction of the poet to the American audiences.

Julian Tuwim’s epic poem “Polish Flowers” was finished during the World War II in New York City, where he managed to escape with his wife, Zofia. Tuwim is best known as a poet of children’s books. He’s just got a kind of genius for rhyming and for nonsense words and for playfulness and this sort of wild, sinister quality that you sometimes get in children’s verse, and fairytales, says Hirsch, He’s somewhat poetically or formally somewhat akin to someone like Richard Wilbur or Anthony Hecht in our tradition. He’s almost impossible to translate.

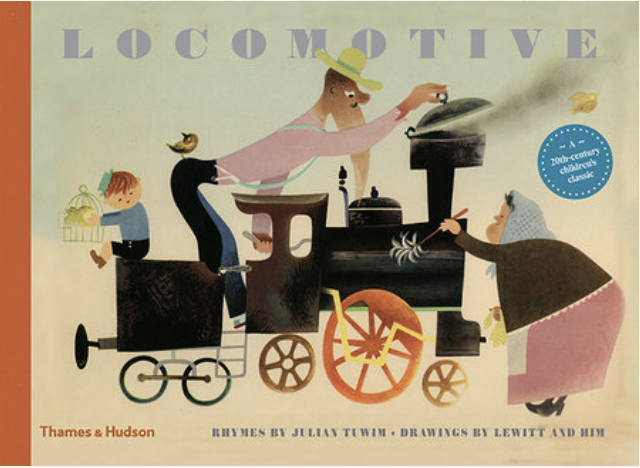

Although, his most popular book Locomotive was translated to English by two English translators: Gutteridge and Peace, the fact that Tuwim himself provided English rhymes to this translation and worked closely with the translators very likely contributed to this masterful translation. “Locomotive” was a bestselling book in Poland in 1930s and remains one of the most beloved Polish books for children.

The first English edition was published in UK in 1940, with illustrations. The same illustrations as original, done by two Tuwim’s friends from Poland who both emigrated to the UK in 1930s: Jan Lewitt and George Him (born Jerzy Himmelfarb in Lodz). Their characteristic style evolved from blending surrealist and cubist tendencies with whimsical humor, they both made the wonderful careers in the UK.

Locomotive, with their illustrations, was published in the US just a few years ago, by the Thames and Hudson, and this Polish masterpiece finds fans among American children now. Locomotive is a little like the children’s book “The little engine that could”. It’s got that kind of charm, that kind of energy, says Ed Hirsch.

In the part two of the video, the 19-year-old Adrian Gnus from Bytom presents a famously controversial Tuwim’s poem called: “To the Common Man” from 1929. The poem, written almost a century ago, is still powerful, and, as Adrian says, “It wasn’t I who found this poem – this poem found me.”

The poem, which a few years ago was set to the music, understands strongly how war benefits those in power and punishes ordinary people. It was criticized as one: too pacifistic, or two: too full of socialist undertones by many groups in Poland. It bears a message which is still relevant. It sounds like a song by Pete Seeger or Woody Guthrie, or a hip hop group, Hirsch mentions.

Julian Tuwim read and understood English, but he was not committed to being in America. While he was living abroad his real life was going on in Poland. After the war he went back to Warsaw at the first opportunity. Tuwim contorted himself to try and embrace the soviet reality and socialist realism. He really tried to believe in the socialist dream, but he increasingly became disillusioned, it was impossible to sustain. And I’m sure that his disillusionment contributed to his to his death. It’s a heartbreaking end to his life. But the work itself is one of the highwater moments of Polish poetry, says Edward Hirsh.

To the Common Man

Julian Tuwim

When the black print sounds alarm

And freshly posted fliers cry

“To the Public,” “For the Troops”

When the glue is not yet dry

And any stud or young recruit

Will take to heart their age-old lie

That it’s time to fire the cannons

To murder, plunder, poison, raze;

When they start to tout “our country”

in a thousand worn clichés

Incite with ostentatious flags

And champion the “historic right”

to every inch, to glory, might

That now has come the time to fight

For our fathers, and forefathers,

Avenge the heroes or the victims,

And when bishop, pastor, rabbi come

to place a blessing on your gun

Because God whispered the command:

go and defend the fatherland

When tabloid headlines spread their noise,

vulgar, nefarious, savage and crude

and frenzied women in wild herds

sprinkle rose petals on our boys

— Hey listen, my untutored friend

Brother from this or another land

Know that it’s kings and portly men

who ring the bells that sound alarm;

And know that it’s bull, a common ruse

When they cry out: “Shoulder arms!”

That for them somewhere gushes crude

Meaning some hefty sacks of cash

And bank accounts do not add up

Or that they caught the whiff of bucks

And that those fat pigs hedged their bets

With an import tax on cigarettes.

Go drum your guns on cobblestones

It is your blood and their crude!

And let your voices linger on

It’s your wage that your blood has won:

“What you’re selling we won’t buy!”

translated, from Polish, by Joanna Trzeciak-Huss

Do prostego człowieka

Julian Tuwim

Gdy znów do murów klajstrem świeżym

Przylepiać zaczną obwieszczenia,

Gdy “do ludności”, “do żołnierzy”

Na alarm czarny druk uderzy

I byle drab, i byle szczeniak

W odwieczne kłamstwo ich uwierzy,

Że trzeba iść i z armat walić,

Mordować, grabić, truć i palić;

Gdy zaczną na tysięczną modłę

Ojczyznę szarpać deklinacją

I łudzić kolorowym godłem,

I judzić “historyczną racją”,

O piędzi, chwale i rubieży,

O ojcach, dziadach i sztandarach,

O bohaterach i ofiarach;

Gdy wyjdzie biskup, pastor, rabin

Pobłogosławić twój karabin,

Bo mu sam Pan Bóg szepnął z nieba,

Że za ojczyznę – bić się trzeba;

Kiedy rozścierwi się, rozchami

Wrzask liter pierwszych stron dzienników,

A stado dzikich bab – kwiatami

Obrzucać zacznie “żołnierzyków”. –

– O, przyjacielu nieuczony,

Mój bliźni z tej czy innej ziemi!

Wiedz, że na trwogę biją w dzwony

Króle z panami brzuchatemi;

Wiedz, że to bujda, granda zwykła,

Gdy ci wołają: “Broń na ramię!”,

Że im gdzieś nafta z ziemi sikła

I obrodziła dolarami;

Że coś im w bankach nie sztymuje,

Że gdzieś zwęszyli kasy pełne

Lub upatrzyły tłuste szuje

Cło jakieś grubsze na bawełnę.

Rżnij karabinem w bruk ulicy!

Twoja jest krew, a ich jest nafta!

I od stolicy do stolicy

Zawołaj broniąc swej krwawicy:

“Bujać – to my, panowie szlachta!”

Julian Tuwim, (born September 13, 1894, Łódz, Poland, Russian Empire [now in Poland]—died December 27, 1953, Zakopane), lyric poet who was one of the leaders of the 20th-century group of Polish poets called Skamander (*).

Closely associated with and cofounder of Skamander, Tuwim began his career in 1915 with the publication of a flamboyant Futurist manifesto that created a scandal. His poetry was marked by explosive energy, great emotional tension, and linguistic inventiveness, demonstrated not only in his lyrical poems but also in nursery rhymes. Among his works published before World War II are Czyhanie na Boga (1918; “Lying in Wait for God”), Sokrates tańczący (1920; The Dancing Socrates and Other Poems), and his most important collections, Słowa we krwi (1926; “Words in Blood”) and Biblia cygańska (1933; “The Gypsy Bible”). Because of his Jewish background, Tuwim fled the country at the outbreak of the war. He eventually spent seven years abroad, first in Brazil—where he wrote his long, quasi-epic poem Kwiaty polskie (1949; “Polish Flowers”)—and then in the United States. He returned to Poland in 1946 but wrote little of poetic value thereafter.

(*) Skamander, group of young Polish poets who were united in their desire to forge a new poetic language that would accurately reflect the experience of modern life. Founded in Warsaw about 1918, the Skamander group took its name, and the name of its monthly publication, from a river of ancient Troy. The group was founded by Julian Tuwim and other poets. Tuwim, a lyrical poet of emotional power and linguistic sensitivity, is best remembered for the collections Czyhanie na Boga (1918; “Lying in Wait for God”) and Biblia cygańska (1933; “The Gypsy Bible”) and for the long poem Kwiaty polskie (1949; “Polish Flowers”). Also associated with the group were Kazimierz Wierzyński, Jan Lechoń (pseudonym of Leszek Serafinowicz), and Antoni Słonimski.

Among sympathizers with Skamander were Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, who had a gift for expressing emotion, and Władysław Broniewski, a powerful lyrical poet who used traditional metres and forms to express concern with current social and ideological problems. A sympathizer of great importance was Bolesław Leśmian, considered the outstanding 20th-century Polish lyrical poet. His symbolic Expressionist poetry—collected in Łąka (1920; “The Meadow”), Napój cienisty (1936; “The Shadowy Drink”), and Dziejba leśna (1938; “Woodland Tale”)—is remarkable for the inventiveness of its vocabulary, its sensuous imagery, and philosophic content.

Biography source: Britannica

More

- Julian Tuwim on Culture.pl

- Julian Tuwim: The Quirks & Dark Secrets of a Polish Jewish Poet

- Locomotive / IDEOLO – Image Gallery

- Yael Vishnizki-Levi’s Locomotive at BWA Wrocław

- There Is No Time to Mourn Your Exhibition During Wartime

- YouTube: Lokomotywa – instalacja Yael Vishnizki-Levi | wideodokumentacja demontażu wystawy

- Julian Tuwim on All Poetry

- Julian Tuwim on YIVO Encyclopedia

- YouTube: The poetry of Julian Tuwim in English translation. Interview with Julia Wilde part. 1

- A big locomotive has pulled into town… Julian Tuwim in English translation

- Polish Flowers

- Weinberg: Symphony No 8 Polish Flowers

- Naxos: WEINBERG, M.: Symphony No. 8, Op. 83, ‘Kwiaty Polskie’ (Polish Flowers)

- Penguin Random House: Locomotive

- YouTube: Julian Tuwim Lokomotywa 1979

- Lokomotywa (“The Locomotive”) by Julian Tuwim, animated and performed by Year 5, Hexthorpe Primary School

- Akurat i Kuba Kawalec – Do Prostego Człowieka (24.01.2015, Kraków, Klub Kwadrat)

- sanah “Warszawa” (J. Tuwim)

- Julian Tuwim and Irena Tuwim Foundation

Moderator: Edward Hirsch

Director: Ewa Zadrzyńska

Cinematography: Jacek Mierosławski

Editor: Anna Jędrzejewska

Executive Producer: Bartek Remisko

Edward Hirsch is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry entitled How to Read A Poem And Fall In Love With Poetry published in 2014. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010) and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker called “a masterpiece of sorrow.” He has also published five prose books about poetry. His latest book of essays, 100 Poems to Break your Heart was published in 2021. He is president of the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in New York City. Currently he is finishing a book of essays called The Heart of American Poetry. It will be published in April to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Library of America. The book consists of deeply personal readings of forty essential American poems. It rethinks the American tradition in poetry. Ed Hirsch lives in New York City.

Lead image: Julian Tuwim, photo: fragment of a post-war photograph from the National Digital Archive collection. Source: Culture.pl.