“The word Faith means when some sees a dew-drop or a floating leaf, and knows

That they are, because they have to be.”

Faith, Czesław Miłosz

Calligrapher:

Hong Houtian 洪 厚 甜 (1963) – Chinese calligrapher and outstanding researcher of Chinese calligraphy. Currently director of the Chinese Calligraphers Association, member of the Regular Script Committee of the Chinese Calligraphers Association, researcher of calligraphy at the China Academy of Arts in the Ministry of Culture, professor of the Calligraphy Training Center at the Association of Chinese Calligraphers, tutor and director of the Central Academy of Fine Arts of the Chinese Democratic League. Tsinghua University tutor and researcher at East China Normal University, Calligraphy Education and Psychology Research Center, professor at Xi’an Peihua University. Vice-chairman of the Sichuan Calligraphy Association, vice-president and secretary general of the CPPCC Institute of Calligraphy and Painting in Sichuan.

Hong is a TV presenter on a channel dedicated to calligraphy. He is an outstanding artist creating highly valued works of Chinese calligraphy in a variety of styles.

Poet:

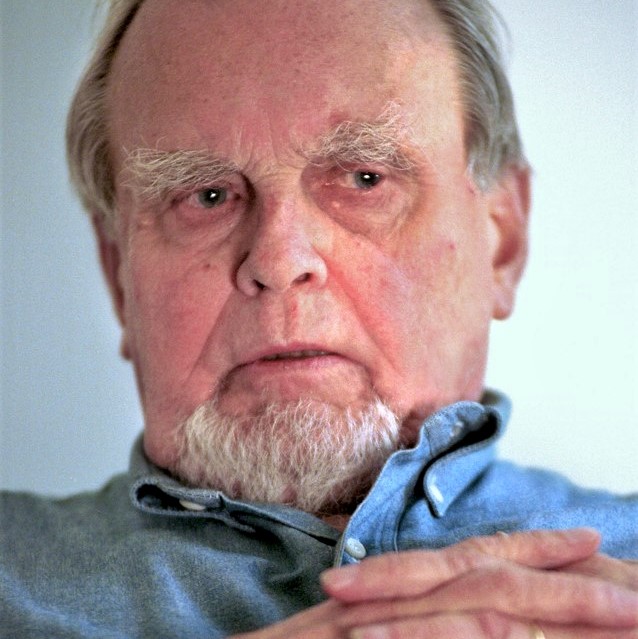

Czesław Miłosz – novelist, essayist and translator. Winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize for Literature. Born in Šeteniai (Polish: Szetejnie), present-day Lithuania on June 30, 1911, died on August 14, 2004 in Kraków.

Background

Czesław Miłosz was the son of Aleksander Miłosz, a civil engineer, and Weronika, née Kunat. He completed his secondary school and university studies in Vilnius, which was then still part of Poland, receiving his law degree from Stefan Batory University. As a student, he belonged to several literary clubs. He made his literary début in 1930 with the publication of Composition and Voyage in the 9th issue of Alma Mater Vilnensis.

He entered the diplomatic service of the People’s Republic of Poland in 1945, but broke with the government in 1951 and settled in France. There he wrote several books in prose. In 1953 he received the Prix Littéraire Européen. In 1960, invited by the University of California, he moved to Berkeley where he lectured as Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures for 20 years, simultaneously writing and translating. In 1971, Miłosz was presented with an award for poetry translations from the Polish P.E.N. Club in Warsaw. In 1976 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship for poetry and an honourary degree as Doctor of Letters from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in 1977; In 1978 he won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature and received the Berkeley Citation (the equivalent of a honorary Ph.D.) that same year. In 1989 he won the National Medal for the Arts.

Fifteen years have gone by since the illustrious writer Czesław Miłosz passed away, although his writing still offers admirers all over the world a window into the delightful brilliance of his mind

First Achievements

Although his works were banned in Poland during his exile in Europe and the US, they reached Polish readers by different clandestine routes, even long before he won the Nobel Prize. Until 1989, most of his publications were accessible in the Parisian emigré journal Kultura or in the underground press in Poland. Winning the prize in 1980 however, made it possible for him to return to Poland after 30 years of absence and it also made it possible for his works to be officially published in his home country again. In a formal ceremony in the middle of the 1990s Miłosz was given a symbolic key to the city of Kraków and a newly-renovated flat. From that time on, he divided his time between Berkeley and Kraków. Over the years his works have been translated into more than a dozen languages.

Critics from many countries, as well as contemporary poets, like Joseph Brodsky, for instance, sweep his literary oeuvre with superlatives. His poetry is rich in visual-symbolic metaphor. The idyllic and the apocalyptic go hand-in-hand. The verse sometimes suggests naked philosophical discourse of religious epiphany. Songs and theological treatises alternate, as in the “child-like rhymes” about the German Occupation of Warsaw in The World: Naive Poems (1943) or Six Lectures in Verse from the volume Chronicles (1987). Miłosz transcends genre. As a poet and translator, he moves easily from contemporary American poets to the Bible (portions of which he has rendered anew into Polish).

As a novelist, he won renown with The Seizure of Power (1953), about the installation of communism in Poland. Both Milosz and his readers have a particular liking for the semi-autobiographical The Issa Valley (1955), a tale of growing up and the loss of innocence that abounds in philosophical sub-texts. There are also many personal themes in Milosz’s essays, as well as in The Captive Mind (1953), a classic of the literature of totalitarianism. Native Realm (1959) remains one of the best studies of the evolution of the Central European mentality. The Land of Ulro (1977) is a sort of intellectual and literary autobiography. It was followed by books like The Witness of Poetry (1982), The Metaphysical Pause (1995) and Life on Islands (1997) that penetrate to the central issues of life and literature today.

Youth and Wartime Europe

He co-founded the literary group “Zagary”, which gathered a circle of Vilnius fatalists in the ’30s. What was the young poet’s fatalism based on? It’s not simply a sharpened sensibility which pushed him and his fellow students to perceive the very tense political atmosphere of the ’30s and its consequences. Their fatalism was rooted in a strong sense of what was to come. Even before the war, in analysing the verses of the twenty-something poet, critic Kazimierz Wyka appreciated the import and quality of the young man’s work:

He rose above the heads of his contemporaries and poetic rivals. The only thing that stands before him is not a measure of his generation (…). An obstacle on the scale of poetry that does not fade, a poetry beyond time.

He also noted the most important element of Miłosz’s works, an element that characterised both his early and later works:

A deep sentiment for the world in spite of what it holds, existing along with the awareness of the cruel evanescence of earthly things.

In 1933 his first book appeared in print, A Poem on Stalled Time which won a prize from the Professional Association of Polish Writers in Vilnius. In 1934 he moved to Paris on scholarship from the National Culture Fund, where he made contact with Oskar Miłosz, a distant relative whose works of poetry had greatly influenced the young writer.

In 1936 he published his second collection of poems, Trzy Zimy (Three Winters), which maintained the fatalistic movement. It was well received and critiqued by some of the major critics of the time: Stefan Napierski, Ludwik Fryde, Konstanty Troczyński, Ignacy Fik.

In 1937 Miłosz moved to Warsaw and worked for Polish Radio. He spent most of World War II in Warsaw working for as a janitor in the University Library and writing for the underground press. After the war he moved to Kraków and joined the staff of the Twórczość monthly. In 1948, he published a collection of pre-war and wartime writings: Ocalenie (Rescue), one of the most significant volumes of Twentieth Century Polish poetry.

Kazimierz Wyka observed how in the face of an apocalyptic vision of the world, Miłosz’s sight is sharpened, more defined, his poetic lexicon taking on a clear concision and a cinematic delivery of sorts, as in Ocalenie:

Miłosz is doubtless a poet of an objective-artistic vision. He’s essentially a plastic realist who observes colours, proportions and shapes in their most objective arrangement. (…) If in spite of this straightforward faithfulness with regard to detail this most individual poetic style doesn’t provide a result that would be equivalent to straightforward description, this is the work of the second, equally important, artistic disposition. I’ll name it – film as a basis for meaning. The laws of cinematic composition, besdes a complete substitution of meaning through imagery, is primarily based on the unexpected. It is only this form of art that makes possible such a broad application of contrasts, passage and unity of images that couldn’t be any more different. At the same time, each individual image was entirely realistic and devoid of any abnormality, while the whole spoke of things much richer than the seemingly simple elements that it was made up of.

Exile

Between 1945 and 1950 he served in various diplomatic posts in New York, Washington and Paris. When he arrived in Warsaw for the Christmas holidays in 1950, his passport was confiscated. After a struggle to recover it, he fled to Paris and requested political asylum from the French government. He settled in Maison-Lafitte outside of Paris in the headquarters of the Literary Institute. He began publishing literary pieces and essays in Kultura. In 1953 the magazine financed the publishing of his volume of essays The Captive Mind, along with a collection of poems Daylight and the novel The Seizure of Power , followed by two more novels: Issy Valley and Poetic Treatise. In the period of the “thaw” around 1957, his poems appeared in the press, but were later taken out of circulation and accessible only through the underground press.

In 1958 he published Native Realm and two years later he accepted the invitation to join the academic staff at the University of California in Berkeley as a Professor of Slavic Languages and Literature. He continued to publish books over the years, such as King Popiel and Other Poems and Gucio Enchanted. In 1965 he published an English-language anthology of Polish poetry based on his lectures: Postwar Polish Poetry. His role as a translator and promoter of Polish poetry, such as that of Zbigniew Herbert is invaluable.

W 1973 his first English-language collection of poems was published as Selected Poems. It gave the American public the opportunity to get to know him as a poet, not just an essayist and translator. A year later he published Where the Sun Rises and Where it Sets. A year later the literary prizes began pouring in, beginning with the Polish PEN club award for translation in 1974 and the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1976, a number of honourable doctorates and in 1980 Czesław Miłosz was awarded the Novel Prize for literature. The recognition of his talent by the world made his works accessible in his native Poland once again.

Native Realm

He returned to Poland in 1989 and began living between the two continents, settled in Berkeley and Kraków, contributing to the Tygodnik Powszechny. He continued to write intesively until the end of his life, publishing three major volumes of poetry in his later years: It (2000), The Second Space (2002) and Orpheus and Euredice (2002).

Czesław Miłosz died on August 8, 2004 in Kraków. He was buried in the Crypt of Church of St. Stanislaus.

The poet’s great oeuvre, created over seven decades, is impossible to describe collectively and concisely. He is a poet of real sensibility and intellect, particularly in his treatment of the everyday, the metaphysics of poetry, morality, history and his own biographical track. Jan Błoński, a critic well-versed in all matters Miłosz, considered his Nobel win and his career in the following excerpt (1980):

The Nobel Prize for Czesław Miłosz is not just a prize for his talent. It’s also a prize for resilience and loyalty to the voice inside that led him through the obstacles of history and his own personal experiences. Miłosz’s sentences are clear, but his poetry is dark, twisted in its richness. If I were to compare it to any instrument, it could only be the organ. Organs imitate all sounds, but they remain organs. They build a musical whole, just as Miłosz’s works build a poetic universe in which irony and harmony curiously co-exist, along with romantic inspiration and intellectual rigor, the ability to employ dozens of images, a characteristic cut of the verse, a remarkable purity of style, devoid of anything superfluous, which paints the world with just a few lines.

Czesław Miłosz’s experiences during the war and loss of his homeland had a great impact on his literary output. In his introduction to re-edition of his anthology of wartime poems originally published in 1942, he writes:Personal experiences of individuals are pushed aside or, rather, there are no exclusively personal experiences: each joy, each suffering of an individual reflects something common and broader; “to be or not to be” pertains in the first place to the national, not individual, existence.

For many people in America, poetry belongs to a sphere of “culture”, a vague notion associated with “leisure”. […] Owing to the tragic history of that nation, a poem, often copied by hand and circulated clandestinely, has been an affirmation of faith in survival and in victory over the oppressors, also by its very nature, a triumphant manifesto of vitality and a bond between ancestors and descendants. Poetry assumed that role already in the nineteenth century, and that is why it was prepared for the ordeals of any modern totalitarian rule. An outburst of underground poetry in Nazi-occupied Poland had, to my knowledge, no analogy in any other country of war-time Europe, with a possible exception of Yugoslavia.

The Writer’s Task

Miłosz’s Traktat Moralny (Moral Treatise) was a manifestation of the conviction that poetry shouldn’t ultimately for linguistic games and the pursuit of “pure lyricism”. Rather, it should aim to measure up to the world on a number of levels, to the politics of the moment as well. Both his treatises – Moral and Poetic, along with his 2001 Theological Treatise, written towards the end of his life – are written in clear, understandable language that is “simple” on the grammatical level, and yet require a great deal more erudition from the reader. Formally, the most complex is the Poetic Treatise, which describes the history of Polish poetry and sets up a confrontation between art with nature. It describes Kraków in the times of young Poland and Warsaw of the interwar period and the third part tells about the German occupation, after which the action is transposed from Europe to America. The whole comprises a multi-layered, collage of narration, full of literary and historical allusions, both outright quotations and disguised references. Here the inspiration was T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, which Miłosz translated during the war. He composes his treatise out of numerous puzzle pieces, citing everyone from Adam Mickiewicz, Tytus Czyżewski and Wallace Stevens to anonymous Polish poets of Jewish heritage, while avoiding sharp segues and one-sided contrasts.

Throughout his works, Miłosz consistently deepens the metaphysical aspect of his poems. He retains his multifarious perspective, while referring to the contrasts between the views of the scientific and spiritual worlds, good and evil, the survival of the weakest and evolution of the species set against religious beliefs. Miłosz captures a very sensual beauty in nature, both wild and domesticated, describing the experience of nature as a moment of ideal joy.

And yet Miłosz does acknowledge the trickery involved in the writer’s task, the ability to manipulate what life brings to us. Ethical issues come up when, as Błoński puts it “the aggressive, cruel, contemptuous ego must fire the lyrical flame”. This ego, self-love, calls for one to divide the world up into “me” and “them”, to consider oneself among the chosen and to treat one’s work as a way of accumulating praise. What drives an artist – is it truly the desire to “file a record” of one’s thoughts or is it simply conceit? Miłosz says it’s both – there’s no way to divide high and now natures. This is tied with a deep-seated feeling of guilt. The only medicine – a bitter one at that – is to become aware of one’s own insignificance. The perspective that the status of, for example, an immigrant and the awareness of the evanescent nature of things, tapers an ambition that has become to sway out of control.

In his foreword to Miłosz’s Selected Poems 1931-2004, published in 2006, Irish poet Seamus Heaney writes that “His intellectual life could be viewed as a long single combat with shape-shifting untruth”. With the conviction that art is the creation of a constant, rather than the pursuit of an incomplete reality, arises the pursuit of a “more voluminous” form – flexible enough to hold as many landscapes and personalities as possible in the memory, creating an encyclopedia of memory. In many of his works, Miłosz acts as a music producer, inviting other artists to contribute to a collaborative project of sorts.

2011 marked the bicentennial anniversary of Miłosz’s birth, commemorated through a series of events falling under Miłosz Year festivities, organised by the Book Institute. As part of the celebrations and the cultural programme of the Polish EU Presidency that year, the Adam Mickiewicz Institute in Warsaw hosted a series of events honouring the poet around the world, including a series of audiobooks in ten European and Asian languages.

Major Works

- Trzy Zimy (Three Winters), Warszawa: Wyd. Wladyslaw Mortkowicz, 1936

- Ocalenie (Rescue), Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1945

- Zniewolony umysł (The captive mind), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1953 (translations: French, English, Italian, Bulgarian, Czech, Greek, Spanish, Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, German, Swedish, Ukrainian, Hungarian)

- Swiatło dzienne (The Light of Day), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1954

- Zdobycie władzy (The Seizure of Power), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1955 (translations: French, English, Spanish, Gujarati, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Malay, German, Serbo-Croatian, Swedish, Hungarian)

- Dolina Issy (The Issa Valley), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1955 (translations: French, English, German, Bulgarian, Danish, Finnish, Flemish, Norwegian, Serbo-Croatian, Swedish, Hungarian)

- Traktat poetycki (A Poetical Treatise), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1957 (translations: Russian)

- Rodzinna Europa (Native Realm), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1959 (translations: French, English, Danish, Finnish, Flemish, Spanish, German, Serbo-Croatian, Swedish, Hungarian, Italian)

- Król Popiel i Inne Wiersze (King Popiel and Other Poems), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1962

- Gucio Zaczarowany (Gucio Enchanted), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1965

- The History of Polish Literature, London-New York: MacMillan, 1969 (translations: Polish, French, German, Italian)

- Widzenia Nad Zatoką San Francisco (A View of San Francisco Bay), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1969 (translations: French, English, Serbo-Croatian)

- Miasto Bez Imienia (City Without a Name), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1969

- Gdzie Wschodzi Słońce I Kędy Zapada (Where the Sun Rises and Where it Sets), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1974 (translations: Serbo-Croatian)

- Prywatne Obowiązki (Private Obligations), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1974

- Emperor of the Earth, Berkeley: University of Cal. Press, 1976 (translations: French)

- Ziemia Ulro (The Land of Ulro), Paris: Instytut Literacki , 1977 (translations: French, English, German, Serbo-Croatian)

- Ogród Nauk (The Garden of Science), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1979 (translations: French)

- Nobel Lecture, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1981

- Hymn O Perle (The Poem of the Pearl), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1982 (translations: Czech, Serbo-Croatian)

- The Witness of Poetry, Cambridge. Mass., Harvard Univ. Press, 1983 (translations: Polish, French, German, Serbo-Croatian)

- Nieobjęta Ziemia (The Unencompassed Earth), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1984 (translations: English, French, German)

- Zaczynając Od Moich Ulic (Starting from My Streets), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1985 (translations: English, French)

- Kroniki (Chronicles), Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1987 (translations: French, Serbo-Croatian)

- Dalsze Okolice (Farther Surroundings), Kraków: Znak, 1991 (translations: English)

- Szukanie Ojczyzny (In Search of a Homeland), Kraków: Znak, 1992. (translations: Lithuanian)

- Na Brzegu Rzeki (Facing the River), Kraków: Znak, 1994 (translations: English)

- Metafizyczna Pauza (The Metaphysical Pause), Kraków: Znak, 1995

- Legendy Nowoczesności (Eseje Wojenne), (Modern Legends – War Essays), Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1996

- Piesek Przydrożny (Roadside Dog), Kraków: Znak, 1997

- Życie na Wyspach (Life on Islands), Kraków: Znak, 1997

- Abecadło Miłosza (Miłosz’s Alphabet), Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1997

- Inne abecadło (A Further Alphabet), Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1998

- Wyprawa w dwudziestolecie (An Excursion through the Twenties and Thirties), Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999

- To (It), Kraków: Znak, 2000

- A Treatise on Poetry, translated by the author and Robert Hass, New York Ecco Press, 2001

- To Begin Where I Am: Selected Essays, edited and with an introduction by Bogdana Carpenter and Madeline G. Levine, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001

- New and Collected poems 1931-2001, London Allen Lane ; Penguin Press, 2001

- Milosz’s ABCs, translated from the Polish by Madeline G. Levine, New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001

- Druga Przestrzeń, Kraków: Znak, 2002

- Orfeusz i Eurydyka (Orpheus and Eureidice), Kraków: WL, 2003

- Second Space: New Poems, translated by the author and Robert Hass, New York: Ecco, 2004

- Spiżarnia Literacka (Literary Pantry), Kraków: WL, 2004

- Przygody Młodego Umysłu (Adventures of a Young Mind), Kraków: Znak, 2004

- Poems (Volumes 1, 2, 3 i 4 – Collected Works), Kraków: Społeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak i Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2000-2004

- Legends of Modernity: Essays and Letters from Occupied Poland, translated from the Polish by Madeline G. Levine, New York : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005

- Wiersze Ostatnie (Final Poems), Kraków: Znak, 2006

- Selected Poems, 1931-2004 , foreword by Seamus Heaney, New York: Ecco, 2006

- Zaraz Po Wojnie. Korespondencja Z Pisarzami 1945-1950 (After the War. Correspondence with Writers 1945-1950), Kraków: Znak, 2007

- Wiersze I Ćwiczenia (Poems and Practice), Warszawa: Świat Książki, 2008

Dąbrowska K., „Czesław Miłosz” Culture.pl, https://culture.pl/en/artist/czeslaw-milosz (accessed: 30.06.2021)