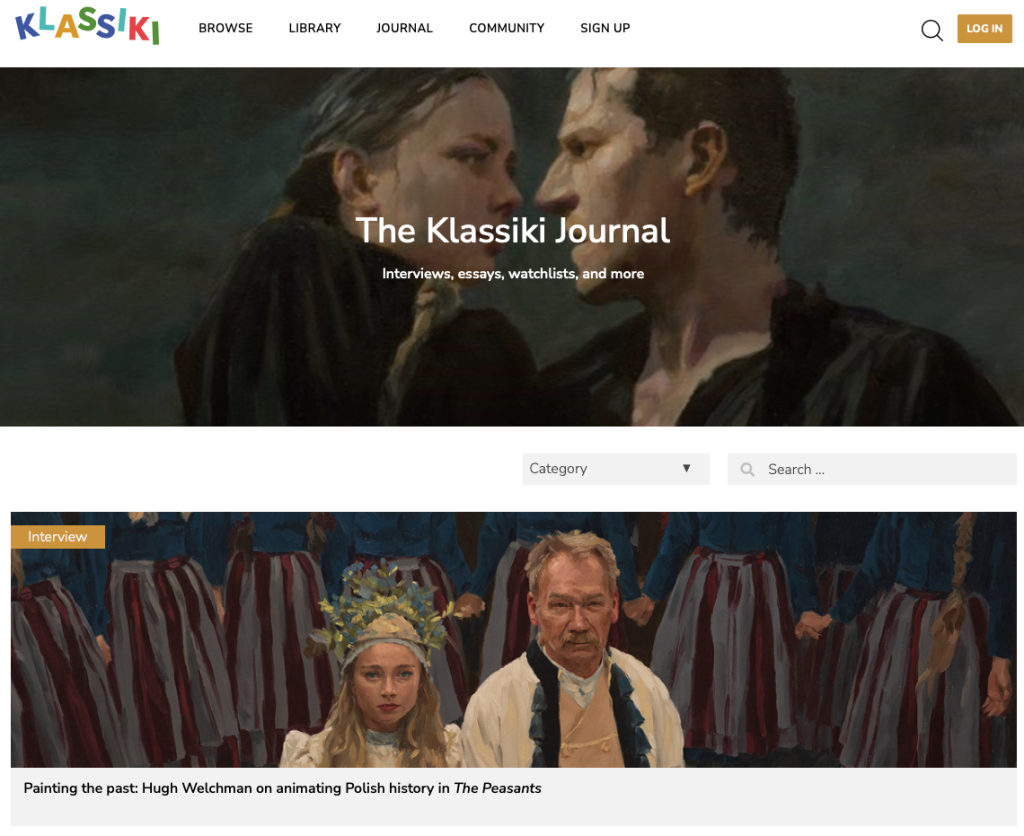

Featured as the Closing Gala film at this year’s Kinoteka Polish Film Festival, The Peasants, transports viewers into the mesmerising painted world of a 19th century Polish village and has received high acclaim for the unique style in which it was made.

The film’s director, Hugh Welchman, first came to wider fame in 2017 with the ground-breaking movie Loving Vincent, the first fully painted animated feature film.

Just like The Peasants in 2023, Loving Vincent could not have been created without the help of 125 artists from all over the world. The film was well received in the cinematic world, premiering at Annecy International Animated Film Festival, and getting the Best Animated Feature Film Award at the 30th European Film Awards in Berlin as well as multiple nominations, including an Academy Award, BAFTA and Golden Globes. However, Hugh Welchman is already a recipient of Academy Award for another animation, Peter and the Wolf, which he received in 2007. The Oxford graduate is also the founder of company BreakThru Films.

And what does he say about the making off The Peasants? How did it all start? Well, quite obviously, with a Nobel Prize winning book – Reymont’s The Peasants that his wife, DK Welchman read at school and then listened to as an audiobook during the making of Loving Vincent. But that is not all – it was Reymont’s thoroughly painterly and more than poetic descriptions of village and peasant life. And this rural life is something inseparably bonded with painting.

When we think about nineteenth-century peasant life, what comes to mind are things like the Pre-Raphaelites, the French Realists, the Realist paintings from across Europe – artists who went out into rural areas to make assertions about national character. We think about nineteenth-century rural life through painting as much as anything else.

– says Hugh Welchman. He also highlights another connection that was used while making The Peasants – it was the use of paintings from artists of the Young Poland movement. The paintings of Józef Chełmoński, for instance, became a benchmark for the visual aesthetics of the film.

The interview is concluded by discussing matters of directorial process, shooting live action footage, Welchman’s critical response to painting images and his choice of the movie source itself – so why The Peasants? And does the movie work in the same way for the Polish and British audience?

For me, it was like reading Great Expectations and finding out that no one had ever done a film adaptation. I thought it was a world-class piece of literature that was unknown outside of Poland: the greatest piece of literature about the peasant experience, which has been part of our lives for 9,000 years. So, I was excited to tell that story and bring it to the world outside of Poland. In Poland, everyone reads it in school – it’s like Shakespeare in Britain. Everyone knows Shakespeare, but that doesn’t mean it can’t still be adapted for film.

Click HERE to read the full interview on the Klassiki website.

Klassiki is an online streaming platform presenting both classic and contemporary movies from Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. From the Polish cinematic library, they offer Bread and Salt (Damian Kocur, 2022), Eroica (Andrzej Munk, 1958), Farewells (Wojciech Has, 1958), Man of Iron (Andrzej Wajda, 1981), Spoor (Agnieszka Holland, 2017), What We Shared (Kamila Kuc, 2021). They also have a ‘Journal‘ section on their website, where they publish interviews, essays, suggested watchlists for special days and ‘Companion’ – a beginners’ guide to the key filmmakers, movements, contexts, and concepts.

Browse their website and engage with a fascinating world of lesser-known cinema.